This post is about sound environments for visual artists, such as painters, photographers, sculptors, etc. I am primarily talking about sound in a gallery display of such art more than, say, a film made about a certain artist’s work or a multimedia immersive work of art. If you read to the end you will learn about workshops and presentations I can do for certain kinds of sonic art that does not require musical knowledge to learn and practice.

Why Sound?

There is a major difference in the way sound communicates as contrasted with visual work. Sound surrounds and may set an emotional “tone” that can enhance appreciation of visual art. Much visual art, such as painting, photographs and sculptures, require a more active role on the part of the viewer to engage with the work. Sound can thus draw a visitor into an exhibit before the visitor starts studying the individual visual works.

So let’s assume you are a visual artist who thinks your art on display could be enhanced by an ambient sonic environment. What are the options?

Play music off of a recording.

This solution can have a couple of major drawbacks. Recordings are copyrighted by both the publisher of the music score and, since the 1970s the recording itself. So even if you decide to use the music of Mozart the particular recording you use of Mozart, if recorded in the 1970s or later, may still be under copyright. Playing music in an art gallery constitutes a “public performance” that requires payment to the copyright holder(s). You might have been in a store that plays a radio station over their PA system, but that is technically illegal if you have not secured permission from the station and possibly paid a royalty.

The second problem with playing recorded music is what I call “the Lone Ranger issue.” It has been said that the true test of an intellectual is someone who can hear the William Tell Overture by Rossini and not think of the Lone Ranger (whose radio show used that music). Familiar music may already evoke memories or emotions in a listener that may or may not be compatible with what you associate with your visual art.

Buy library music.

There are companies that will sell you, often at low cost, music from their library that is already cleared for public performance. Some of it might work for you, but I should note that I once judged a film festival where three of the films, each created by a different director, all used the same library piece. That kind of thing detracts, I would think, from the originality of your presentation.

Compose and perform your own musical compositions.

If you have learned music and can compose and perform, this could be a good solution as it can link your visual art to your musical art. The American painter, Mark Khostabi, for example improvises compositions at the piano and the American photographer, William Eggleston, composes both at a piano and a keyboard synthesizer.

But what if I don’t play an instrument and don’t know how to compose?

Now we are getting to the main thrust of this post. There are forms of music and sound art that can be learned and used even by people with no real musical background. I am referring here to musique concrète and soundscape art. I have touched upon this is my last post about the history of electronic music but now want to explain more.

Both musique concrète and soundscape art are forms of sonic collage. In the visual arts collage became a major art form starting early in the 20th century. There are major visual artists whose work is collected by museums who have created collages by taking images from a variety of sources, often magazines and newspapers, cutting out elements and pasting them up as visual compositions. For examples see:

https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/3318/top-10-collage-artists-hannah-hoch-to-man-ray

Sound collage did not start until the mid 20th century when tape recording became available. A few early experimenters did work by cutting disks, but the form is really one that emerged with magnetic tape and now with digital sound recording.

There are really two forms:

Musique concrète

This really started in the 1940 in France when a radio engineer, Pierre Schaeffer, made experimental compositions by recording sounds from various sources, then processing them by changing the tape playback speed, reversing the tape, filtering certain frequencies, adding delay, etc. This was developed even more by a colleague of his, Pierre Henri, who had a long life and a major catalog of musique concrète composition. The name of the art form is based on the fact that the creator is working directly in sound and is not creating a “score.” A score is really a just directions for a performer to interpret. Concepts of traditional music, such as notes, scales, harmony, notation, etc. are not relevant to musique concrète composition. One works concretely in sound.

Another aspect of this kind of sound collage is that the sounds are usually processed so the source of the sound is not always recognizable. What a microphone records is just basic material that is usually heavily transformed by the musique concrète process.

Soundscape art

Whereas music concrete was first developed in France, soundscape art is associated with Canadian artists such as R. Murray Shafer, Hildegard Westerkamp, Barry Truax, Claude Schryer and others.

In this form of sonic collage there is no attempt to distort the original sounds. There is a documentary aspect so, for example, a soundscape piece might be a collage based on the sounds of Vancouver, Canada or other places.

For some visual artists, soundscape art could provide an effective sonic ambience. If a photographer presents a series of photographs of, say, busy New York streets, then a soundscape of the sounds of busy New York streets might make an interesting sonic accompaniment.

How does one create sonic collage?

Before the invention of the computer based digital audio workstation — often now just referred to by its initials, DAW — musique concrète could involve physically cutting tape, pasting it back together, copying a sound to a different tape machine and similar tedious time-consuming processes. Before capable personal computers came on the scene I once met a musique concrète composer who was creating a composition where each note sung by a female singer would start off as a sung note, but the end of each would morph into the tail of the same note played on a piano. This required taking tiny bits of tape, often just a few inches long, and splicing them. His piece took weeks to create. On a modern DAW it would take only a few hours.

If a visual artist decides to create musique concrète on a computer, he/she will need a capable computer and software capable if processing bits of sound. These can include professional software for sound composition, such as Logic Pro for the Macintosh or Acid Pro for a Windows machine. Quite a few processes can be learned even using the free DAW, Audacity (available for both Mac and Windows).

Simply layering recorded sound into “tracks” and mixing them can be quite easy on most DAWs. This makes them suitable especially for soundscape collages where one can go out and record parts of an environment on a small handheld recorder or even a good quality cell phone, copy the sounds to a computer, edit the most interesting and important sounds, then mixi them in the DAW.

Musique concrète is a bit more difficult on the DAW as one has to learn how to process the sounds and perhaps even buy “plugin” software to expand the processing capability of the DAW. How fast this can be learned depends on the technical background of the user and their experience with complex computer software. Still, it is way easier and faster than the old tape slicing methods of early musique concrète.

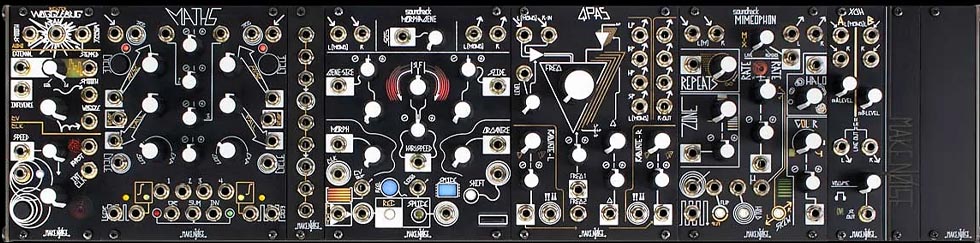

Lately I have been experimenting with the Make Noise Tape & Microsound Music Machine Eurorack Modular Synthesizer System. (Make Noise is the name of the company). While most synthesizers are designed to generate sounds internally, this system is designed especially for musique concrète, where sounds are put in the synth and processed in real time by patching in different processing modules. No need to use a mouse, just knobs like early synths, such as the Buchla. No keyboard. (see picture below)

There is something very satisfying in real time music creation as compared with the old tape splicing method or mousing around in a DAW.

WORKSHOPS

I am proposing to present two difference kinds of workshops to introduce people, especially visual artists, to the value of sound art based on sound collage.

The introductory workshops would be about 2-3 hours with some hands-on work by the students (and thus limited to a fairly small number of students per session).

In the Soundscape workshop I would invite participants to use their cell phones or small handheld recorders (such as the Zoom or Tascam models) to record an environment then show them how to edit, layout and mix those soundscapes fragments in a DAW. Participants who wish to bring their own laptop computer and DAW software would be welcome. The purpose in the three hours would not be to create a finished soundscape, but to introduce participants to the basics. I am available also to offer workshops over a period of days that go into more depth.

For the musique concrète workshop I would again ask participants to record short isolated sounds (not broader ambient environments as with soundscapes) on their cell phone or a portable recorder. As a group we could then use some of the sounds and the Make Noise synth to process the sounds in real time. I would also demonstrate a few processes than can be done on a DAW for participants who would want to ultimately create their work that way. Again, I propose a short 2-3 hour introductory workshop but am open to conducting longer workshops.

I will begin offering some of these in my own studio in Poughkeepsie, NY starting late spring (as I will be moving my studio in March to larger space) but I can come to your city or organization to do a custom workshop. Pricing will vary upon location, travel involved, etc. For more information contact me at info@sandbookstudio.com.

And be sure to read my previous post: ELECTRONIC MUSIC — THEN/NOW

Leave a Reply